Warning: This post is long. While working through this massive server upgrade/migration process, tears were shed, many cuss words were said, along with a general feeling of frustration, which ultimately culminated into extreme happiness once the migration was completed. The scale and complexity of the implementation factor into the length of this post, and I’ll share my thought process on how this was executed, so here goes.

Last year, when we upgraded to SQL Server 2017 we didn’t make any changes to the operating system on our main production servers. They were Windows Server 2012 (not R2), and we knew that moving to another operating system would be painful because it would involve tearing down each of the clusters, rebuilding them, and potentially having extended downtime - which we really can’t have. It sounded too difficult at the time, so it was punted…again.

When I was mapping out projects for 2019, at the top of my list was to move from Windows Server 2012 and move to Windows Server 2019, because ‘hey, it’s 2019 let’s move away from 7 year old OS’. From the start, it was obvious this would be extremely complicated, but why not start the new year off with a crazy project that gets us in a position to move to SQL Server 2019. I had never done anything like this before, but in January, I started working out how we were going to upgrade our existing production SQL Servers from Windows 2012. And in this very long post I explain all my planning, testing, unexpected issues, and implementation of this move.

Reasoning

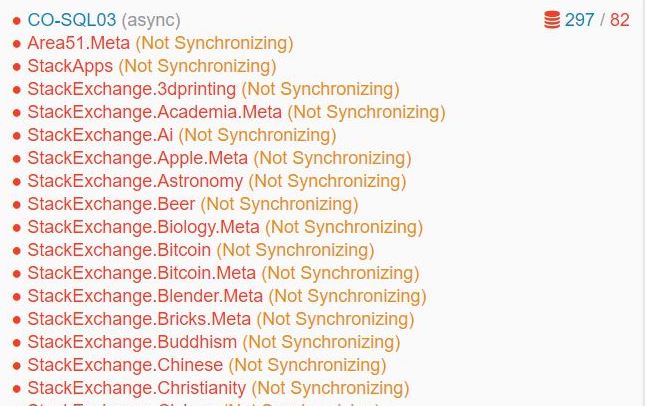

My first step was to identify the benefits of migrating. I would be spending a considerable amount of time on the project, so it was important to know what we would gain from the upgrade. There were two obvious wins 1) moving away from a 7 year old operating system, and 2) it also would allow us to move to SQL Server 2019 (yay… more upgrades). However, the biggest benefit we were hoping for, was an improvement with our availability group log transport throughput. Our current production clusters each have 3 nodes - 2 (primary and local secondary) in New York (actually New Jersey) and 1 (remote secondary) in Colorado - and we tend to see significant delays and non-synchronizing databases in Colorado. Upgrading from 2012 to Windows 2016+ would get us gains in performance, and hopefully reduce some of our syncing issues. For me, that would be a huge plus, as I wanted to avoid seeing stuff like this repeatedly during the week:

Phase 1: Lab Testing…All The Things

I’m incredibly lucky to have a lab environment to play with. At the start of this project, I had two lab Windows Server Failover Clusters (WSFC) - each with 2 nodes that were running Windows Server 2016, SQL Server 2017, and each cluster had availability groups (AG), as well as a distributed availability group (DAG) between the two clusters. Since I didn’t want to destroy these clusters for the test, I needed to create new servers for testing.

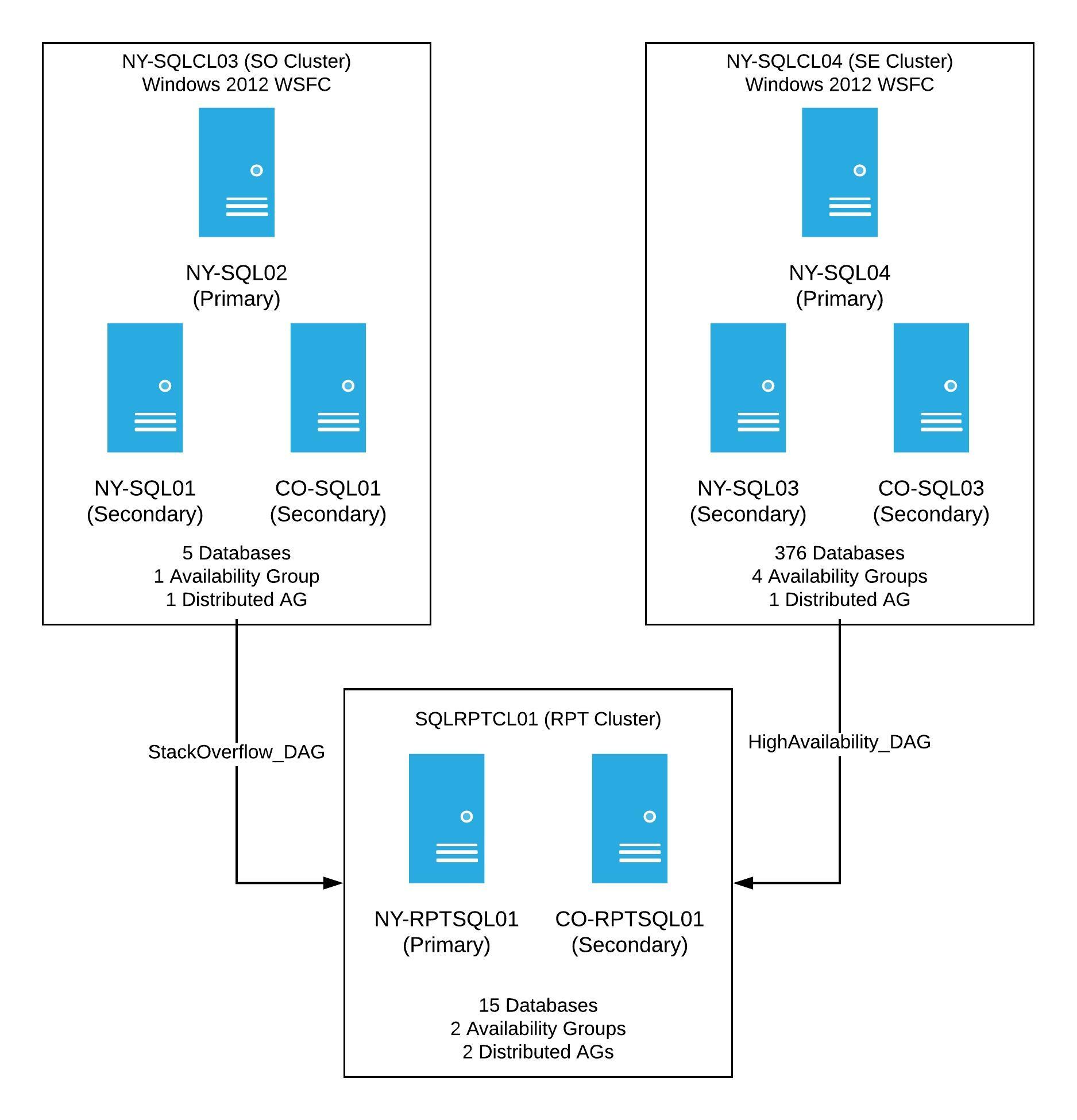

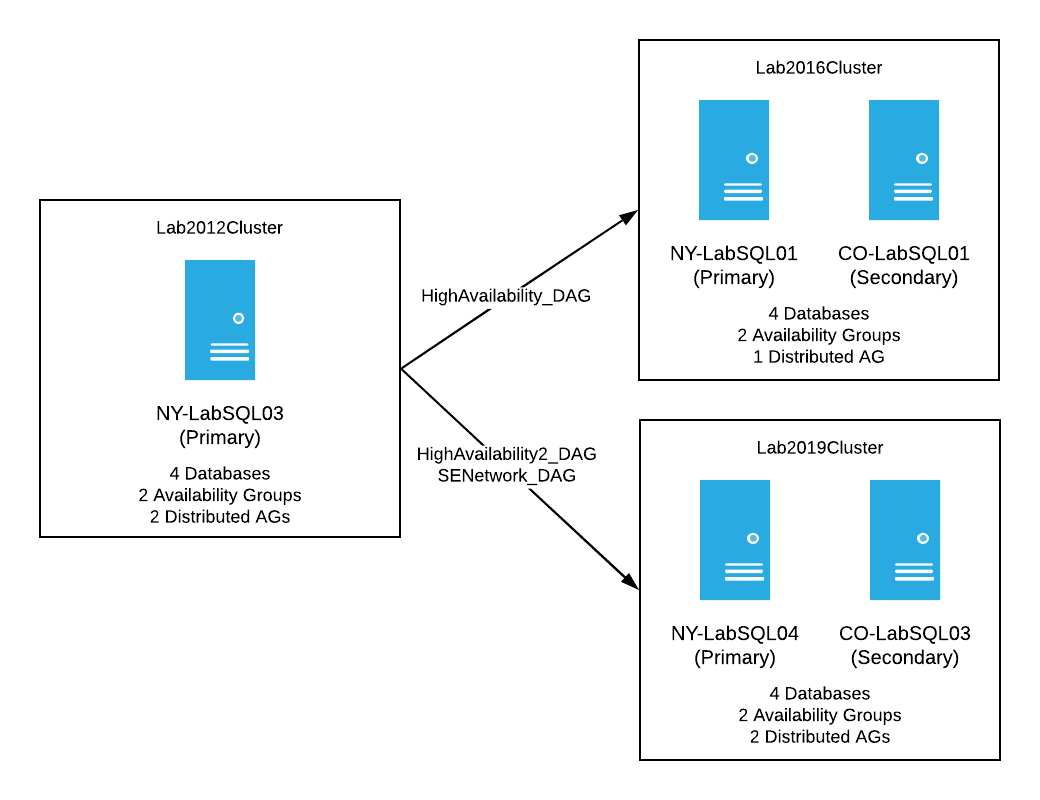

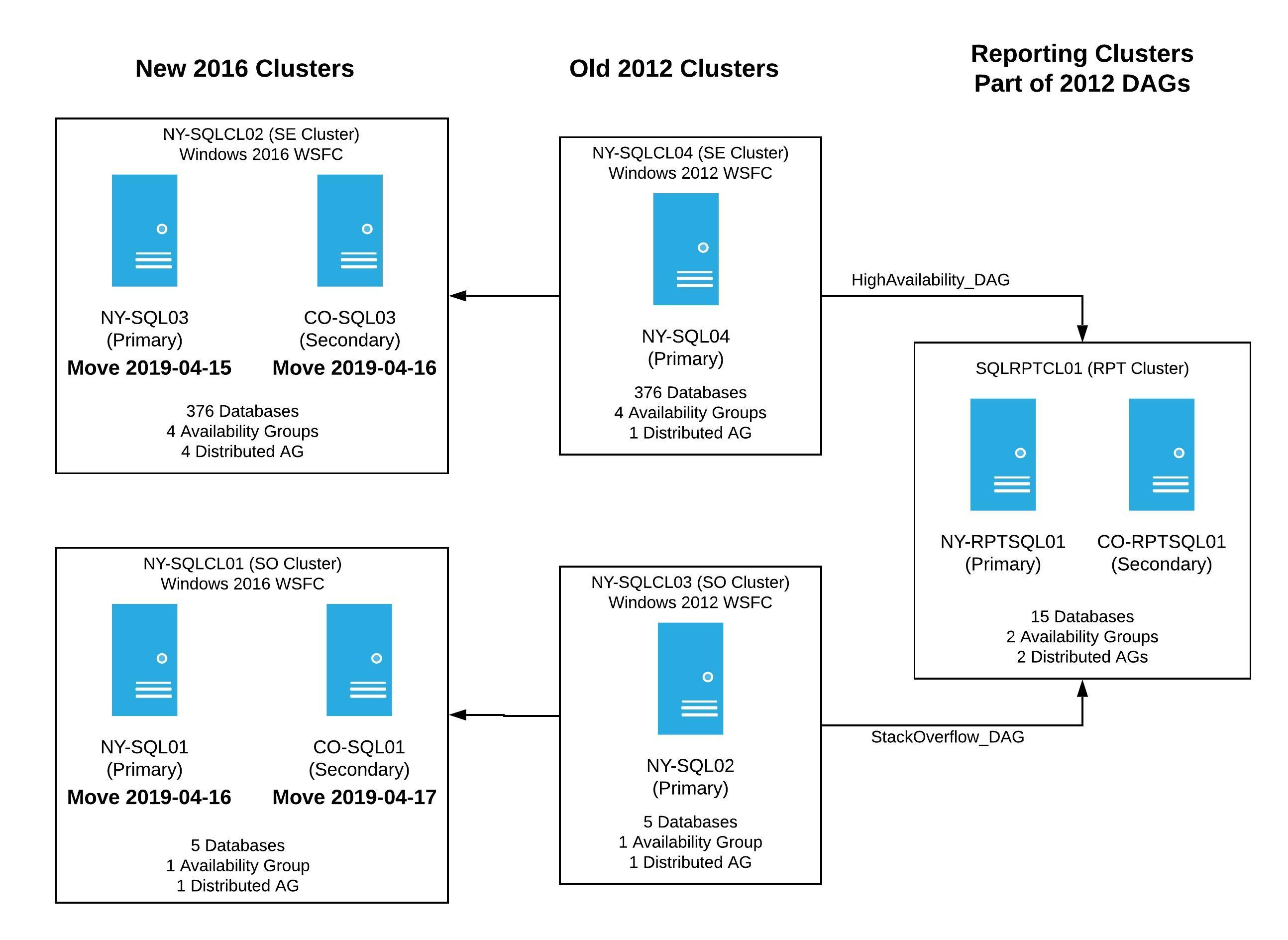

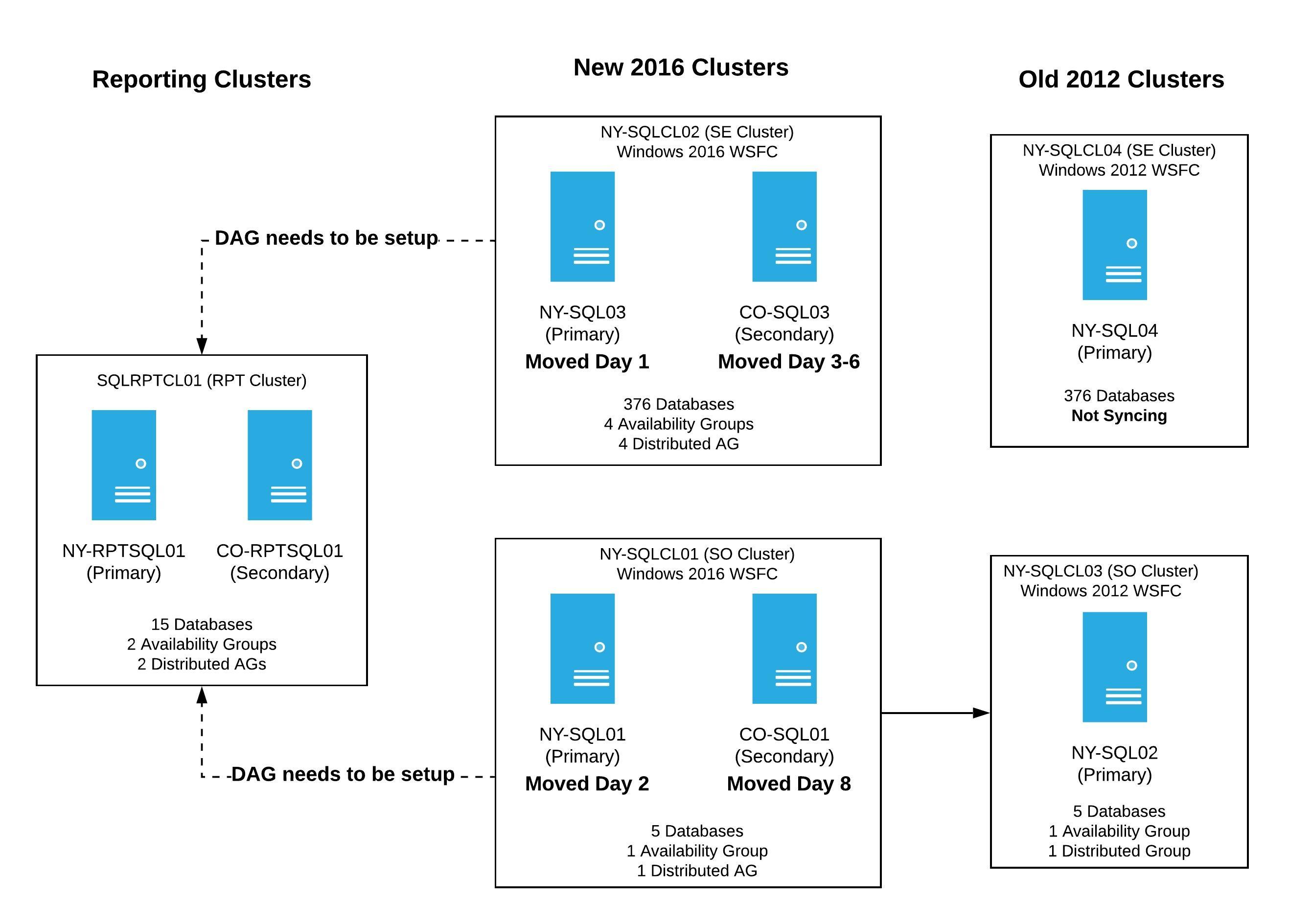

My goal was to replicate our production set-up on a much smaller scale. From there, I’d work through different scenarios to get to the final desired result. The 2012 production clusters looked like this:

Production had two WSFCs running Windows Server 2012, each with 3 nodes. Both clusters have at least one availability group, as well as one distributed availability group going to a reporting cluster. Once this project was complete, the new clusters would look the same, however, these would have a new OS, new cluster names, and when finished, the primary SQL Server in each availability group would be the current NY Secondary.

In order to properly test, I needed 3 servers running Windows Server 2012. Well, guess what? We didn’t even have a way to install Windows Server 2012, and no longer had an image of the software. This left me hunting for a copy of it. Eventually I got one, but then our deployment process needed to be setup to work with 7 year old software. Once all those bits were in place, I was able to spin up my 3 servers to test with. At this point, I had a new 2012 cluster with 3 nodes (2 in NY, 1 in CO). All were running SQL Server 2017 with 2 availability groups, one AG that was limited to this cluster, and a second AG that was modeled after one in a distributed availability group.

The Will This Even Work Test

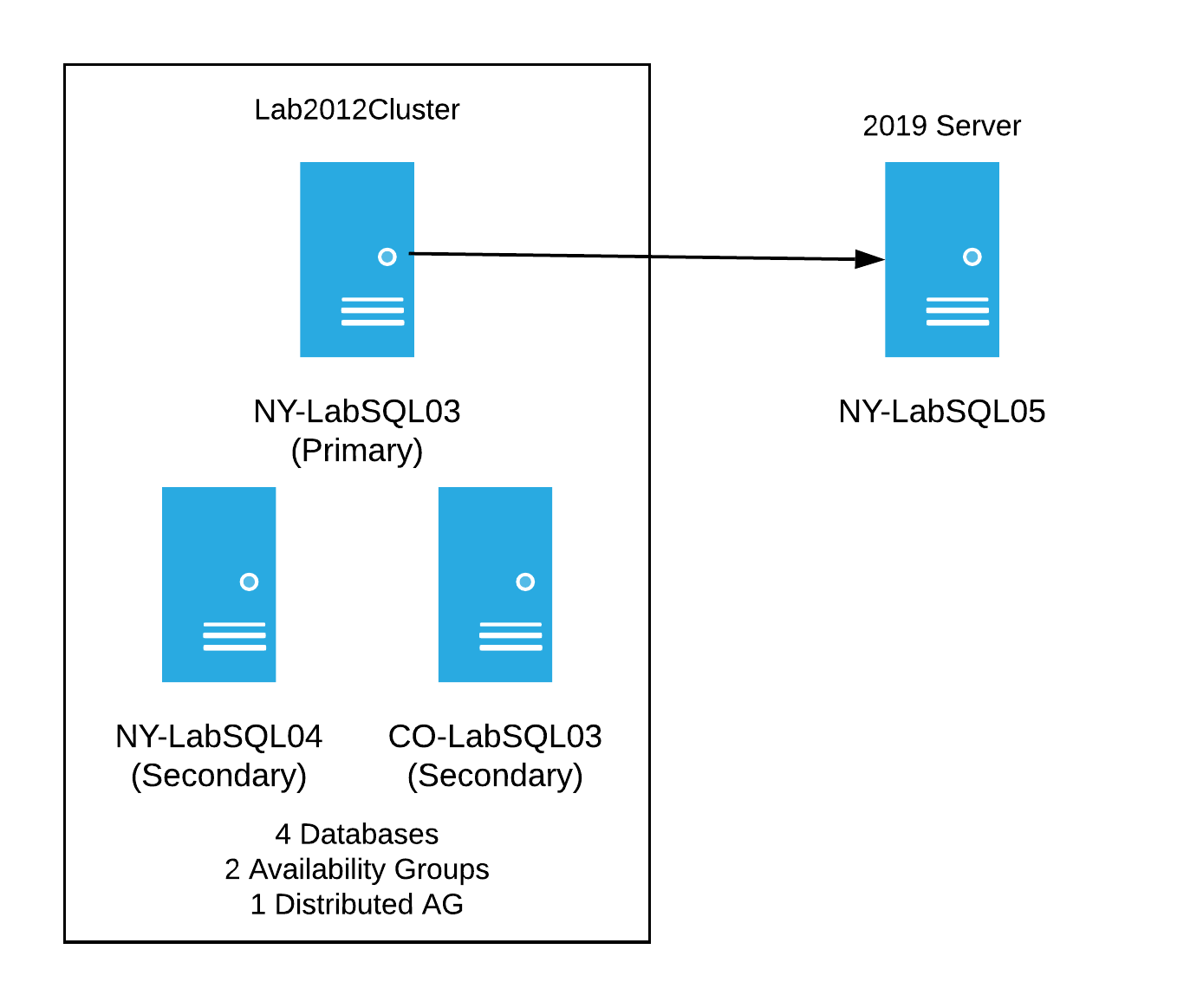

Before I started breaking this new test cluster, we had the idea of creating another server with Windows Server 2019 to see if it would work with the new lab cluster - basically, a test to see if the data would sync. I spun up another new server; this time it was on a fancy new operating system, Windows Server 2019, with SQL Server 2017 and was all ready to start testing. The goal was to insert the 2019 server into the mix with 2012, so it would receive data from the old server cluster. I wanted it to look like this:

Considering I had no idea what I was doing, I tried many things to get this to work. I even tried things I knew wouldn’t work just to cross it off the list of things tested. Here’s a brief list of some of the things I tried:

- Putting the 2019 server into the existing 2012 cluster - as expected, this fails due to the operating systems being different

- Attempted to just add it to the existing AGs when not being in a cluster - this fails because it’s not in a cluster

- Created a separate single node cluster for the 2019 server and attempted to add as a replica to the AGs - this fails as well

None of these things worked. I was beginning to wonder how we were going to do this. My next test was to create a new distributed availability group for each existing availability group, using that as a way to insert the 2019 server into the mix. I finally hit on something that worked for the single server. After creating a new DAG between the 2012 and 2019 cluster, I had data syncing between two clusters on different operating systems. I was ecstatic to get this to work with one server, but how would I do this with the 3 servers in a single cluster, with all the AGs and distributed AGs already in play?

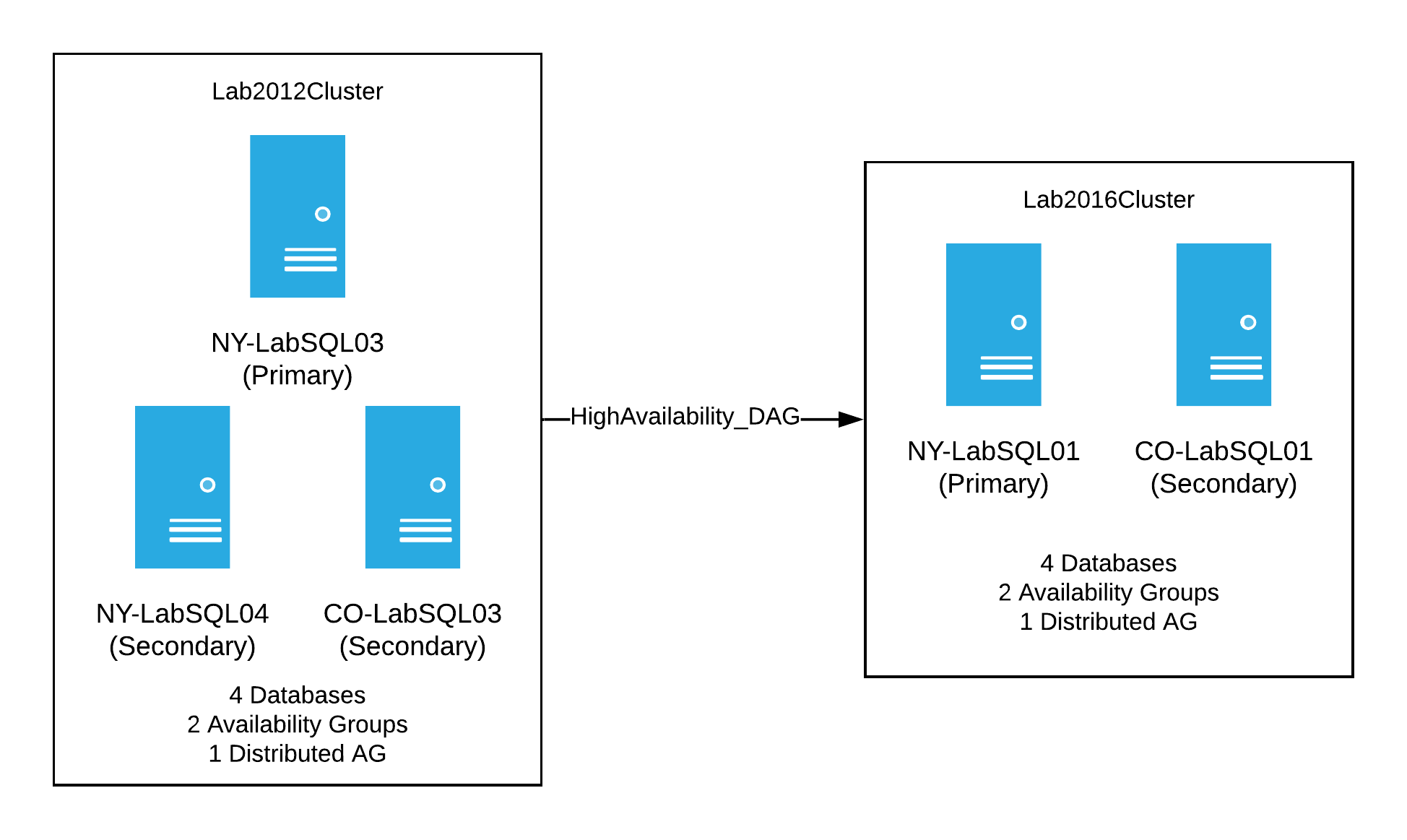

The Mock-up Production Test

Once I knew I could have clusters with different operating systems, synchronizing data via distributed AGs, I needed to attempt this with the new 2012 lab cluster. Since it was already working as a stand-alone cluster with SQL Server running, I wanted to set up a test that was as close as possible to what we have in production. I needed a replica of our reporting cluster. A bell went off in my head, ‘Ding! Ding!’ I had an existing 2016 cluster in my original lab environment - that would be perfect to use for this.

My plan of attack for this test was to first setup a DAG between the 2012 cluster and the original lab cluster running on 2016. This would be similar to what we had in production at the time. Basically we’d have the following:

When that was setup and synchronizing, I had a decent, albeit, small version of our production setup. It was now time to start breaking things. My thinking was to start with the NY secondary server and perform the following steps:

- Evict it from the existing 2012 cluster

- Rebuild it with the Windows Server 2019

- Create a new WSFC with one node

- Install SQL Server 2017

- Finally, create new distributed AGs from the old cluster to the new one to sync the databases with that AG

My next step was to do the same thing with the CO secondary in the 2012 cluster. The difference being, it could just be added as a node to the new WSFC, and as a replica to the AGs in the new cluster. At this point in the process, I’d have the old 2012 cluster with a single server sending data to two clusters - the mocked up 2016 reporting cluster and the new 2019 cluster. Visually it’d look like this:

Before upgrading the last 2012 server, I would need to perform a failover of the distributed AGs from the 2012 cluster to the new 2019 cluster. In looking at this, there was one glaring problem…the reporting cluster. If I performed a failover of the distributed AGs to the new 2019 cluster, the reporting cluster would stop getting data. I saw there were two options:

- Perform the failover and let the reporting cluster fall out of sync until I could get it everything back in place

- Move the reporting cluster and it’s distributed AGs to the receive data before I failed over to the new 2019 cluster and “hope” things just starting syncing again.

Either way, the databases on the reporting cluster were going to fall out of sync, so I chose the first option for the lab.

Now that the decision was made, it was easy peasy to finish the move in the lab. There was only one server left in the old cluster, so my steps were to failover the distributed AGs to the new 2019 cluster (yes, I tested failing back just in case), destroy the 2012 cluster, rebuild the server with Windows 2019, add it to the 2019 WSFC, install SQL Server, and add it as a replica to all the AGs. Yay, everything was done! What’s left was just a bit of clean-up of the reporting cluster distributed AGs, and then I was ready to move to production with the plan.

I spent the next week writing up all the steps to move to production. There were a lot of moving pieces for production. I had to move the following:

- 2 WSFC

- 6 servers with new OS, fresh SQL Server installs

- 5 availability groups with a total of about 385 databases

- 5 AGs means 5 temporary distributed AGs to help with the move

This also meant we needed new IP addresses for the clusters, AG listeners, as well as new names for the clusters, AGs, distributed AGs, and listeners. During my testing I discovered that you can’t use the same names for these objects, even when they’re on different servers, which resulted in a lot of legwork to get prepped for the move to production, but I was ready…or so I thought.

Phase 2: The Part Where I Broke Dev

Pretty much the entire month of January, I tested and worked through how this would be done in production. I originally targeted February to start the production servers. I was wrong.

During the final stages of review, a suggestion was made to test an upgrade to Windows Server 2019 on a few development servers, to ensure we wouldn’t hit any hiccups with the OS when it went to production. Our main development servers for Core Q&A have the same hardware and set-up as production, but don’t run any AGs - the servers only have copies of the databases for development. In testing the OS against these servers, we’d be able to perform some load testing, and I could make sure our deployment process of the OS would work.

I picked three servers to test against - two VMs and one physical server. We use Foreman to automatically (re)build servers, which made the process relatively painless to deploy and rebuild servers. Since Windows Server 2019 had never been deployed, it wasn’t setup in Foreman. This meant I had to upgrade the servers by hand, as an in-place upgrade - this was done on the two VMs. Aside from some minor issues, everything went according to plan. The OS deployed just fine, and I easily reinstalled SQL Server across the board. The servers were back up and running within a few hours.

Next, it was time to deploy Windows Server 2019 to a physical server. That’s when everything went off the rails.

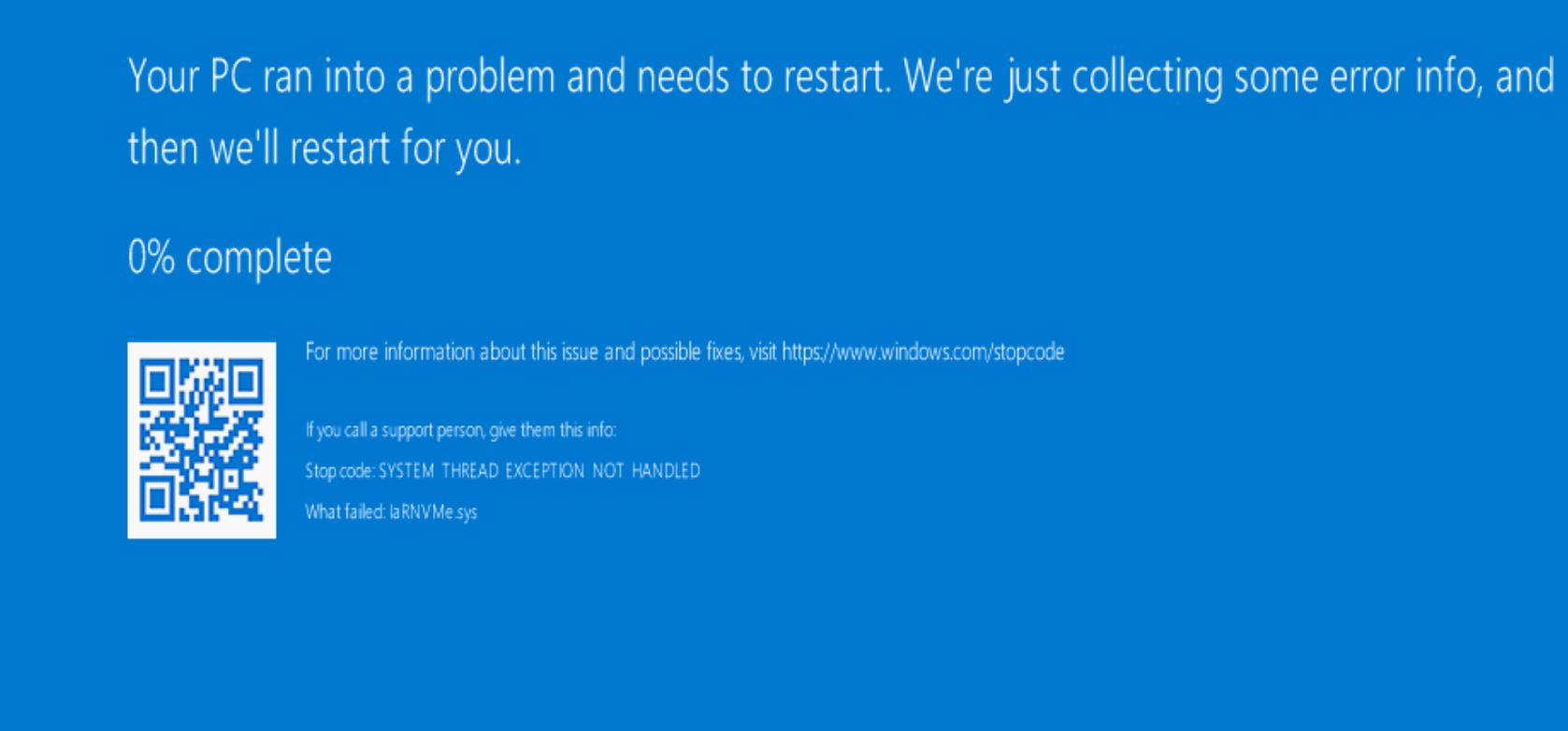

As I mentioned, our main dev servers have similar hardware to our production servers, which means we have a drive for the OS, a data drive for SQL with NVMe/PCIe, and possibly a third drive with spinny disks. The physical server I tested the upgrade against had all three drives. I kicked off the rebuild, and about two hours into the process the dreaded blue screen of death hit:

Very quickly, we spotted the issue. The NVMe drivers didn’t work for Windows Server 2019. Oh crap. Thankfully, I have awesome teammates who jumped into a hangout and helped debug. After discussing, we attempted to upgrade the driver to the new one, and, of course, that bombed. Then one of the NVMe drives looked like it failed. After some poking, the “failed” drive came back online and we were able to get the server back to its 2016 state pre-upgrade attempt.

Now what?

We still wanted to move to 2019, but the new driver wasn’t working with our NVMe RAID, which meant time to contact both Dell and Intel. With their help, we might be able to get the correct drivers and software to work with our drives and the NVMe RAID. Eventually, we got the necessary bits and had the new drivers in place with software that recognized our RAID. Next, it was time to test another 2019 deployment. After two hours into rebuild #2, I was staring at a 45% completion:

I tried not to worry and went on to other tasks. At hour 6 of being stuck at 45%, I was concerned. Even though this deployment hadn’t finished, it was obviously stuck, so we decided to attempt another fresh rebuild…#3.

When rebuild 3 began, everything seemed to be going ok. Once up and rebooted, we were back to a 2016 Windows Server. WTH?!?! This time we also had a freshly formatted 2TB NVMe partition…meaning all of our SQL data on the NVMe drives was gone. We decided to try once more, this time disabling the PCIe slots in the BIOS and trying another fresh rebuild - this time #4.

Our confidence level in moving to Windows Server 2019 was quickly dropping, but we wanted to see if we could get it to work. Our 4th rebuild, finally got 2019 installed on the server, but we hit another issue. When the PCIe slots were re-enabled, we only had 2 disks show up in the RSTe manager and in disk management on the server, but everything was showing in the Device Manager.

Ugh, why are they not matching? There were so many weird problems with this server.

The next step was to send someone to the data center to physically unplug & drain the power from the box to see if the issues with the PCIe slots would sort itself out - we have done this in the past and it worked. Unfortunately, our trick of draining power didn’t work. We still only had two disks show up…sigh. That means time for another rebuild.

This time we were going to try to rebuild the server to 2016 with the old drivers for the SSDs to see if we could at least get it back to the state it was before the upgrade to 2019. The hope was that if we rolled back the driver, the PCIe slots might come back to life and the drives would miraculously work again. Off to rebuild #5.

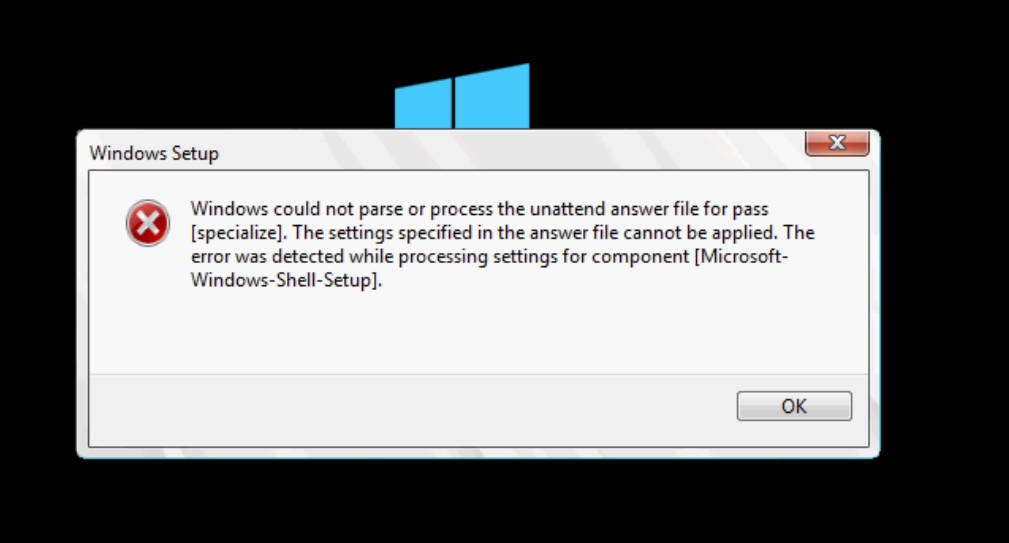

After fighting with the server to use the older drivers, I finally got them installed and kicked off another rebuild. Unfortunately, this time we had a failure because the deployment failed to join the server to the domain and we couldn’t login to the server…seriously, the server was possessed.

Yay, another rebuild (#6) to try to get it on the domain, with Windows Server 2016, and old drivers so the SSDs work. Guess what? This failed again, due to issues joining the domain. Again, my teammates rescued me and got into a hangout to beat the server into submission and get it joined to the network. Once it was finally joined to the domain, there was another freaking issue.

It was getting ridiculous with this server. I found a way to hack it back into submission because at this point anything was worth trying. The OS finally installed, but we had two very dead SSDs. They were showing up as 0GB. We tried upgrading firmware…nothing worked. The drives were dead. It was time to open a ticket with Intel since the drives were still under warranty. It was now a waiting game, until Intel confirmed the drives were fried.

While we were waiting for new drives from Intel, my teammate, Mark Henderson, spent time fixing up our Foreman deployment to work with 2019 and to bypass the NVMe drives when installing an OS. You know what that means…more rebuilds. Actually 3 more - one to 2016, one to 2019, and then one back to 2016 for a total of 9 rebuilds of Windows (so far) on a single server.

You might be wondering why we went back to 2016 after we finally successfully installed 2019?

This was done because our confidence level in using 2019 with our SSDs was pretty much gone. Intel no longer makes the drivers public, and referred us to Dell, and then Dell sent us back to Intel - it was a back and forth game - which wasn’t a good position to be in for production. Combined with multiple failures and dead SSDs, we didn’t feel comfortable moving forward with Windows Server 2019 on our production servers. We couldn’t risk killing our SSDs due to the install. We knew that 2016 worked with them because Dev had been using it for years, and we’d get the benefits of moving off of Windows Server 2012, so we made the decision to skip Windows Server 2019 at this time.

About 2 weeks later, we finally had new SSDs. It was now time to get them installed and test the deployment process again. Here we go with rebuild #10. Time to hopefully get a clean install of Windows Server 2016 - I spoke too soon. The rebuild failed. No, I’m really not joking.

On top of using Foreman, we use Puppet to get our servers in a desired state - the failure this time appeared to be due to a Puppet issue, but there was, of course, nothing in the error log that pointed to the issue. We had yet another failure, and we wanted one clean install on this server, meaning no issues whatsoever. That meant another rebuild to see if we could get an install with zero errors. This server wasn’t quite ready to be nice, we hit various issues with the install process and it took 4 more times before we had a clean build of the server for a total of 14 times!! After all the issues, we finally had a dev server almost back to its original state - Windows Server 2016, now it just needed SQL Server and that’s super easy to install, right?

I moved on to installing SQL Server 2017 again, and since this server was terrible on every level we ran into more issues. I have a couple of PowerShell scripts that I use to install SQL Server which work all the time, except on this server. There were errors installing the SqlServer module, then there were really odd issues with SPNs for the server not being tied to the proper account and the server was associated to me - it really was cursed. After a ton of more issues (you really don’t want details on everything), we finally had a dev server back in place. All databases were restored, and things were working again.

Now what? Well, we had another dev server to test this against, this time our NY dev server. We decided to try a clean install against that server, but first we spent about a week trying to fix all of the weird issues we were hitting with the CO dev server…yes, that means more rebuilds. Once everything was working without issue, it was time to move to NY Dev. Our NY Dev server is critical path for pushes to production, so that rebuild involved a bit of juggling, but eventually I was able to rebuild it and yay, there were no issues with SSDs or really anything else that would be a blocker for moving to production.

By the time I finally got done with NY Dev, it was about 2 weeks into April, that means it was over two months of working through all the issues with the development deploys. I was totally ready to move this project along and touch production.

Phase 3: Time For Production

It was now into April, and I thought this was going to be finished in February, so you could say I was extremely anxious to finish this project and move on to other things. Since our development environment was finally done and it appeared that our deployment process was working, I revisited the plan I wrote in January for our production environment.

I opened the Google Doc that I initially wrote and started expanding it into a very detailed plan on the deployment process. I spent several days writing out each step for every server we would be moving around. I tried to include everything I could think of. The step for each server even had the code that would be executed on it. This was probably the most detailed plan I had ever written, I attempted to cover everything I would think of. Nick Craver, then added more details because the connection strings for each application would be changing due to moving to new listeners.

I was ready to go. We were ready to go. The runbook had about 35 pages of notes and code to execute in the entire plan.

Every server had a detailed list of steps including obvious things to more complicated pieces. Inside of the document, you could look up any server and find a list similar to this:

Server Name (Date)

- Stop Transaction Log backups on primary

- Remove read-only routing from the AGs (this is done on the primary) - including code snippet to run on the primary

- Flush connections in the app

- Disable full backups on primary

- Remove server from the existing AGs on primary

- Evict server from current cluster

- Setup server in Foreman for 2016 deployment, kick off the rebuild

- Make sure puppet is up and running after the rebuild

- Once done rebuilding, add Failover Cluster role to the server (this forces a reboot)

- Create new WSFC (only on the first server in the cluster)

- Once the Cluster Object is created in AD, then move it, if needed, to the proper Cluster Objects OU

- After cluster creation, verify the IP addresses are correct and edit them, as needed

- Make sure the WFSC cluster object has permissions to create/delete computer objects in AD

- Install Dell NVMe tools

- Install SQL Server – if the tempdb is still located on D:\Data - delete all the files first

- Turn on trace flags – restart SQL service

- Execute scripts to add logins / users / stored procs / linked server

- Create New AGs

- For each AG create new temporary distributed AG aka the TAG (our temporary distributed availability group for the migration) - created on the current primary and then the secondary

- At this point everything should be syncing to the newly built server, and it’s a single server on its own cluster

- Re-create sql jobs

- Disable backup jobs for user databases

- Re-enable backup jobs on primary server in old cluster

While the steps were different for each server, this was basically what I needed to do. By the end of Wednesday, April 17th, 2019, if we were lucky I’d have moved 3 servers to the new clusters, and would have SQL Server installed with everything syncing as I tested. The goal by the end of Day 3 was to have things looks a bit like this:

I announced we were going to start on Monday, April 15th and finish the following week. I felt pretty confident that we were ready for production. There was absolutely no way we’d have issues like we did on the development servers, right? Wrong. Oh did we ever hit unexpected issues.

Day 1

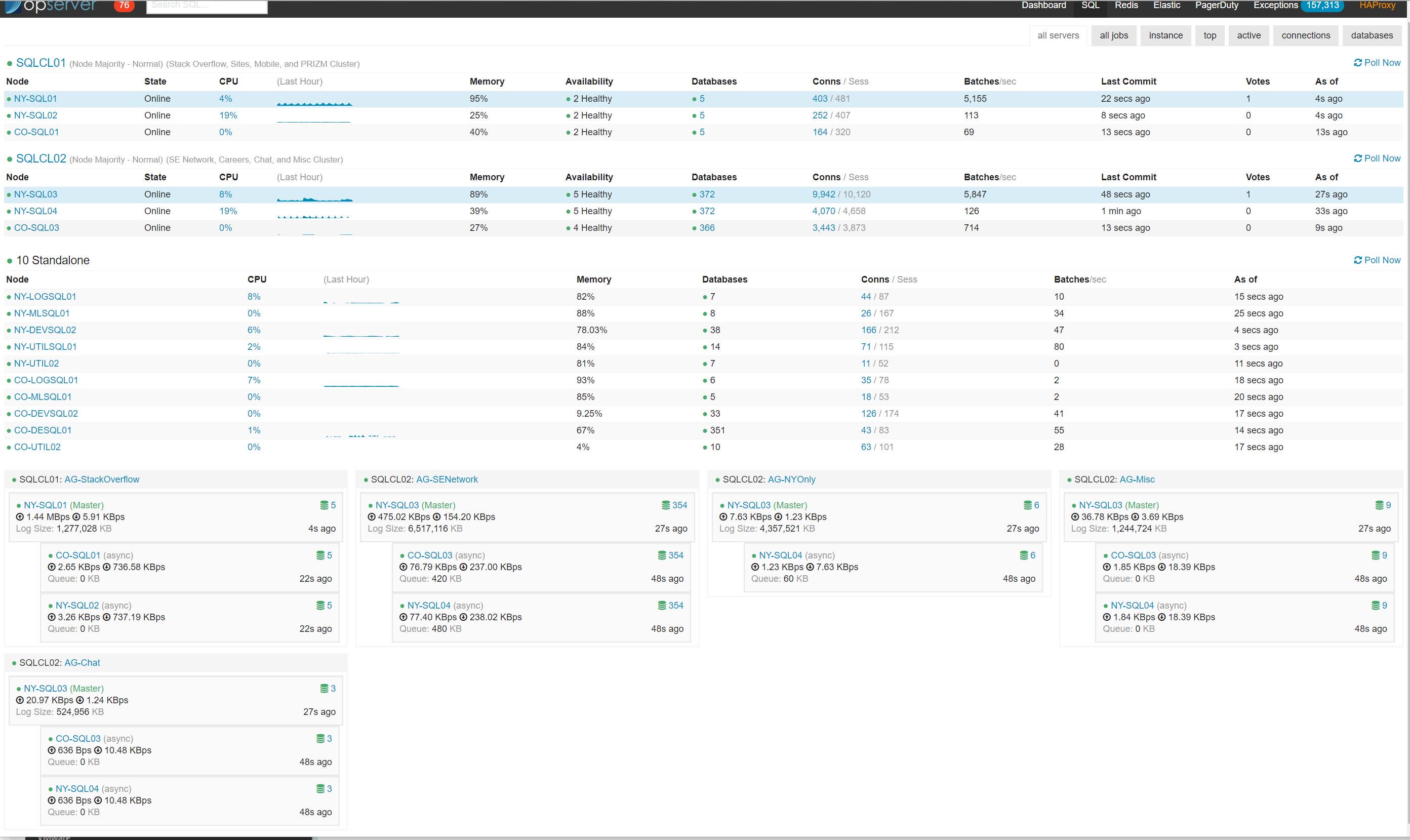

The very early morning of April 15th rolled around, and I kicked off the plan for the very first server, NY-SQL03, the NY secondary in the SE cluster. Everything went according to plan, Windows installed, SQL Server installed, new cluster set-up - all 4 temporary distributed availability groups (aka our TAGs) were in place. We had all databases syncing and reporting green in Opserver at the end of the end. Day 1 done, so far, so good - one server down, 5 more to go.

Day 2

The day started just as early because if things went well, I was going to tackle two servers, NY-SQL01, the NY secondary in the SO cluster, as well as CO-SQL03, our Colorado remote secondary in the SE cluster. I kicked off the rebuild on both servers, and NY-SQL01 was back in working order within a few hours with everything syncing as we expected. The other server, CO-SQL03, was another story.

While CO-SQL03 was rebuilding, I started to notice some weirdness…yes, weirdness (that’s a technical term, right?) with the server I rebuilt the day before - NY-SQL03. As a quick reminder, this server was currently the only node in the new 2016 cluster. It had about 375 databases which were in 4 availability groups, and 4 distributed availability groups - the distributed AGs were being used to keep the data in sync between the old 2012 cluster and the new cluster. The breakdown of number of databases per AG was:

AG-NYOnly- 6 databases syncing via distributed AG -NYOnly_TAGAG-Misc- 10 databases syncing via distributed AG -Misc_TAGAG-Chat- 3 databases syncing via distributed AG -Chat_TAGAG-SENetwork- 354 databases syncing via distributed AG -SENetwork_TAG

Now, that you’ve had a reminder of what we had on the server, let me explain what I meant by “weirdness”. One of the primary ways we monitor our servers is through Opserver. After hours of what appeared to be databases syncing without any issues I started to notice that we were hitting blocking when trying to get the status of the availability groups and databases when querying the DMVs as Opserver does. And not just a little bit of blocking. This was significant blocking on everything. We couldn’t get any details in SSMS on the databases or availability groups. If you attempted to open any details in SSMS (AGs, databases), it would lock your session and you’d have to kill it in Task Manager.

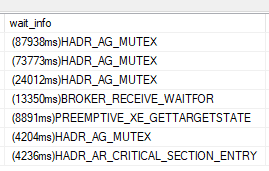

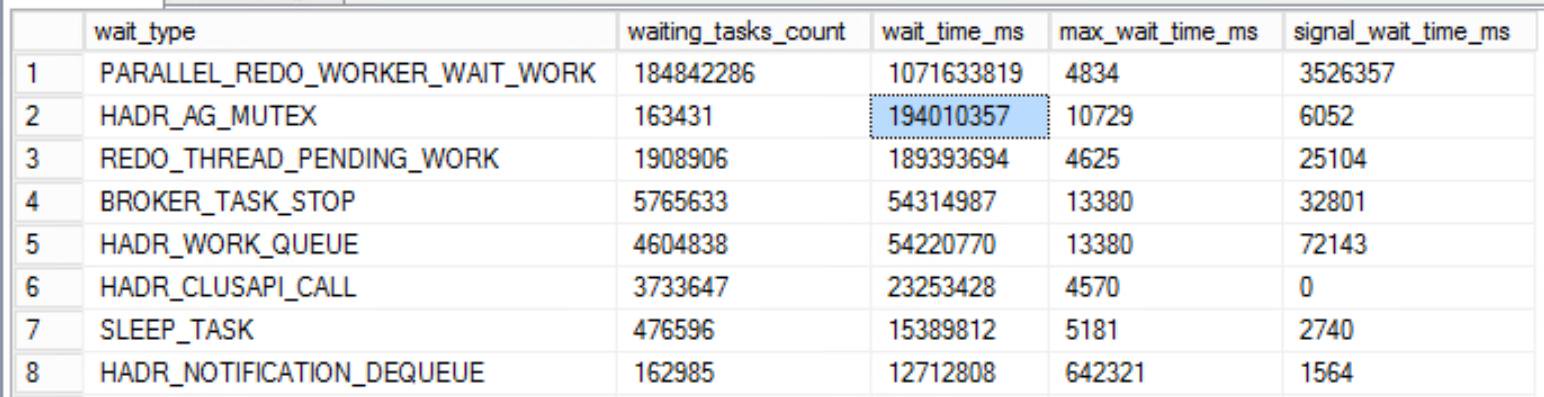

Everything we tried to get the state of the AGs was locking up, even directly querying the DMVs in SSMS. We were seeing tons of HADR_AG_MUTEX waits:

In addition to the locking, we noticed a lot of inconsistencies in what was being returned via the queries. One minute it looked like the availability groups were fine, the next it was in a not-synchronizing state. We realized that we couldn’t trust the state of the AGs on the server. After hours of looking at this and trying to debug, I decided to drop our temporary distributed AGs, the TAGs, to see if rebuilding them would work because nothing else was working at this point.

I started recreating some of the TAGs to see if things would sync, as I created each one, they would start to sync, but we were still hitting significant waits and locking.

We tried restarting the SQL Server service. We tried stopping the availability groups in the WSFC. We were seeing errors in the logs that the AGs were in a failed state, we couldn’t query the DMVs, we didn’t have any idea what was happening. It looked like the 2 distributed AGs that were small were working, even though checking their health was very slow.

It was time to try to recreate the SENetwork_TAG, the one with the 354 databases. Early on in this process, we stopped Transaction Log backups and Daily Backups, so we had a couple of options:

- Autoseed the databases as you can with availability groups

- Use the old backup of the SE Network databases (the one from before we started the migration process), and restore it to the NY-SQL03 server, letting it get caught up with the AG syncing

- Take a new backup of the databases in the AG, restore it to NY-SQL03 again, and then join it to the AG to let things start syncing.

Considering the slow querying of the DMVs and the AG health, we went with number 3. I took a recent backup of the database from the primary server in the old cluster and restored it to the new server with NORECOVERY. The thinking was that this would prevent overloading the server by automatically trying to seed 354 the databases all at once. Once all the databases were restored, we would execute the following on each one:

|

|

Problem was, this was really slow. Doing this for each database was taking a couple of minutes per database and we have 354 of them. The waits we were hitting were downright unbelievable:

The amount of time to execute the command against each database exponentially increased as we were adding more and more databases. It was going to take hours to get through them all. It was super late in the day, and Nick and I had been debugging and working in a hangout for many, many hours. Nick quickly wrote a script to loop through all of the databases in the SENetwork_AG and execute the SQL above. This automated the process which allowed it to run overnight, and more importantly allowed us to step away from our desks after far too many hours. We hoped everything would be in the AGs in the morning, so we could debug some of the issues we were seeing and potentially move forward with the upgrades.

Days 3-7

Yes, that really says Days.

The script eventually finished and we had all databases in the AG, however, we were still seeing tons of waits. I was chatting with some of the users on our Database Administrators Stack Exchange site, and there were suggestions to disable parallel redo on the server, as well as other things. We tried everything we could think of, and still didn’t know if things were syncing because we couldn’t get an accurate read from the DMVs or get passed the waits. Since nothing was working, it was time to open a ticket with Microsoft. Our ticket was opened, the server was creating plenty of mini-dumps that went sent along with memory dumps, and now it was time to wait for help.

A quick aside: while waiting for things to get moving with Microsoft, we attempted to get CO-SQL03 back in a good state. We take local copy-only backups in Colorado, so we don’t have to deal with trying to move terabytes of datafiles from NY to CO in the event of an issue. All of that typically is fine, but due to the issues, we ended up being down for far longer than expected. This meant our backups in CO were very far behind the current state of things in production. In order to get CO-SQL03 in working order, we needed to copy all of the database backups from NY to CO, which was going to take a really, really long time. Good thing we weren’t in a hurry, huh? We kicked off a process to copy the current backups from NY and get them moved to CO. With Shane Madden and Nick Craver’s quick thinking, we copied all of the files in less than a day. Now that we had good backups, I restored all of the databases in NORECOVERY so they would be ready whenever NY-SQL03 box was back up and running.

Our Microsoft ticket was forwarded and we began working with one of our DBA.SE users who happens to work for Microsoft, Sean Gallardy. At this point, it was time to go back to the regularly scheduled painful upgrade process. Based on the memory dumps, one of the first things Sean suggested was to make sure that auto-seeding of the databases in the SENetwork_TAG was disabled, so we executed:

|

|

While this prevented the databases from automatically being seeded, it didn’t resolve our issue. We were still failing to sync databases on the new cluster, and we were dropping mini-dumps like crazy on NY-SQL03. It was back to the drawing board with ideas to fix all the things. Nick and I got onto a really long hangout with Sean (thanks Sean), to debug and work through various ways to fix the problem. Eventually, Sean suggested that we try the following:

- Destroy the temporary distributed availability group (TAG) for the

SENetwork, since that was our problem child - Destroy the availability group on the new cluster

- Manually restore the databases to both NY-SQL03 and CO-SQL03 in a restoring state

- Recreate the temporary distributed availability group for the

SENetwork - Add each database to the availability groups on both NY-SQL03 and CO-SQL03 very slowly so they could sync

That’s what we did. Another really slow process, and when I say slow I mean 2-4 databases at a time - and we had 354 to add, so it was painfully slow, but it worked.

We were hitting a bug with SQL Server. The bug had to do with distributed availability groups that had more than 15 databases and, of course, we had that. Our distributed availability group contained 354 databases and it couldn’t handle that many, resulting in it timing out. We got a workaround by following the steps above were able to move forward.

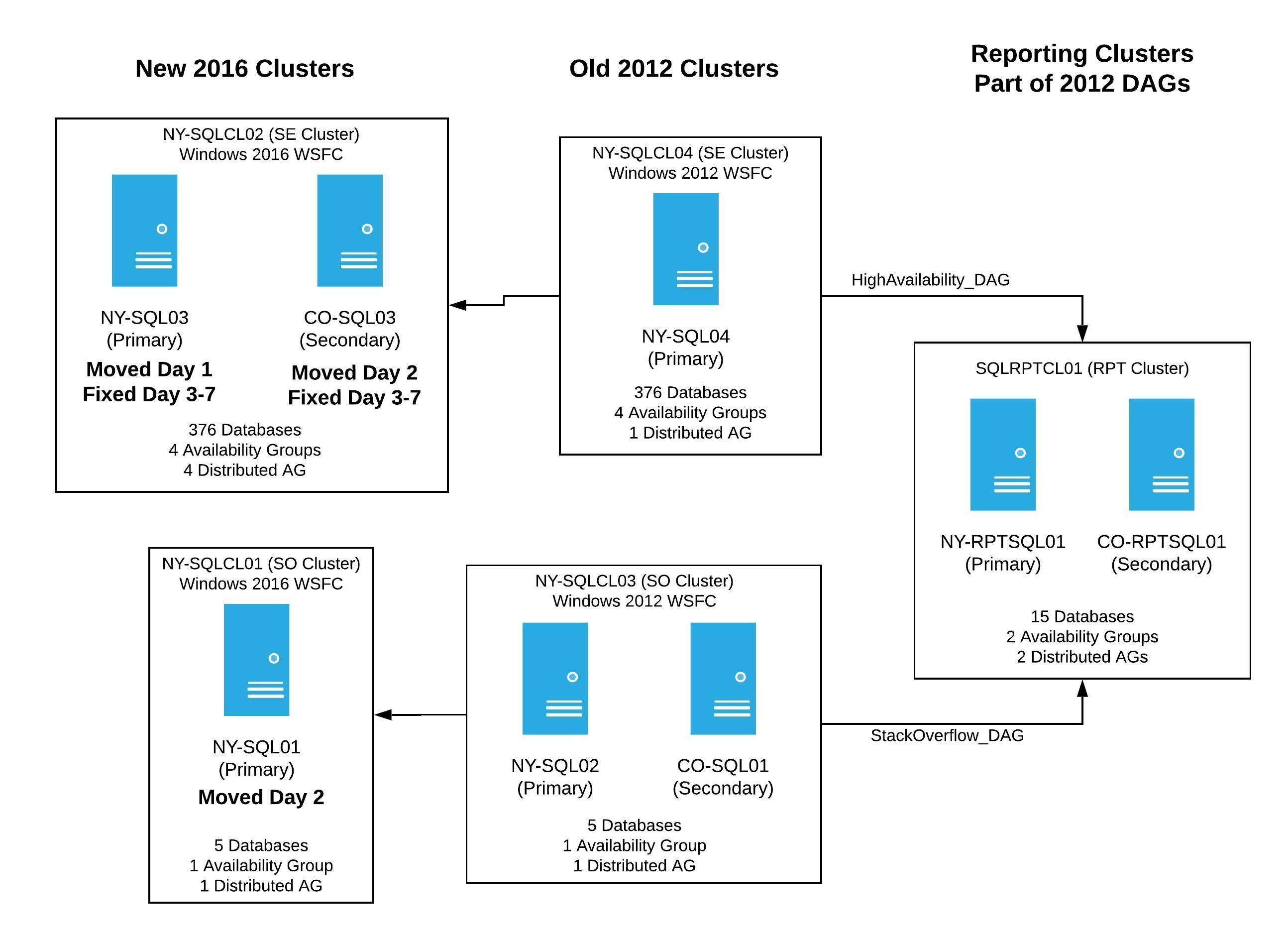

By the end of the week we had two new clusters up and receiving data from the old 2012 clusters. It was now time to finish moving pieces around so we could perform the failover of the temporary distributed availability groups. Even though we lost several days working through bugs, we were in a better, more stable state and could plan the date of the failover - if everything else went according to plan, it would be in just a few days. To help visualize where we were at the end of this week, our servers were in this state:

After a pretty quiet weekend, only a few minor hiccups with data syncing, we were ready to pick up and go full steam ahead to wrap things up.

Day 8

Monday morning rolled around and there were 3 servers left and one huge failover to do. Surely, we had hit all of the bugs and it was going to be a clear path to the finish line, right?

I started the day by evicting CO-SQL01 from its old cluster and kicking off the rebuild process. Ugh, and I hit some issues. The automated process, Foreman, didn’t want to work without some poking and prodding to get it moving, then the server didn’t want to find the Windows Updates it needed, but eventually the rebuild finished. I was able to install SQL Server, restore backups in a NORECOVERY state, apply all the transaction logs to bring it up to current state, and just like that, we had syncing data.

We finally had 4 servers in the new clusters, and they were reporting green everywhere.

Day 9 - Failover Day

The big day was here. It was time to perform the failover of 5 temporary distributed availability groups, with hopefully very little downtime. I previously tested the whole process in the lab, but had never done this in production. And considering all the problems we hit up to now, I was feeling just a wee bit stressed out.

The morning of the failover, we spent time going over the steps that would be executed that night. We wanted to make sure that we had accounted for all of the application side changes that were needed as well. The complexity of this whole thing wasn’t limited to just failing over the SQL Servers. We also needed to rebuild and push out new versions of all of our applications and services due to changes to the connection strings.

You might be wondering why we needed to do that? All of our application connection strings point to global listeners and since we had new clusters with new AGs/distributed AGs - they all needed to be created with new listeners (IP Addresses) and new names. This means that prior to the failover, the applications were pointing to the old listeners. In order for them to work when we failed over, the apps needed to be rebuilt to production to point to the new listeners.

We also needed to be very deliberate about the order of things on the failover day.

The first thing we considered were exceptions. We have a database called NY.Exceptions which we use to capture errors that occur throughout the network. We needed to be sure it would still capture errors, in the event the failover failed. To do this, we removed the NY.Exceptions database from both the old and new AGs and made sure the database was writable on both the new and the old clusters. We also added both databases to our monitoring in Opserver to catch lingering applications pointing to the wrong place. This would let us collect errors, even if things went wrong with a failover.

Next, we had to think about how to push our application changes to production. We use Team City to deploy our applications, which has a database on SQL Server. We needed to be sure that Team City was available before we moved forward. As a result, the NYOnly_AG was the very first one to failover. We pushed a change to the connection string from SQL-NYOnly_AG to SQLAG-NYOnly and built out the application. Once that was done, it was time to do the distributed availability group failover.

Based on my testing and the Microsoft Docs performing a failover of a distributed availability group is a manual process. The code needs to be executed on the current primary server, validated, then more code has to be executed, then validated, and repeat until it’s all done. In my huge planning document, I wrote all the code to perform the failover steps. Now it was time to execute them. Since we were going to be failing over the temporary distributed availability group called, NYOnly_TAG we executed the following steps:

-

On the current global primary server in the DAG (NY-SQL04) change the DAG to

SYNCHRONOUS_COMMIT1 2 3 4 5ALTER AVAILABILITY GROUP [NYOnly_TAG] MODIFY AVAILABILITY GROUP ON 'NYOnly_AG' WITH (AVAILABILITY_MODE = SYNCHRONOUS_COMMIT), 'AG-NYOnly' WITH (AVAILABILITY_MODE = SYNCHRONOUS_COMMIT ); -

Verify the commit state is

SYNCHRONIZEDon the global primary (NY-SQL04):1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10SELECT ag.name , drs.database_id , drs.group_id , drs.replica_id , drs.synchronization_state_desc , drs.end_of_log_lsn FROM sys.dm_hadr_database_replica_states drs INNER JOIN sys.availability_groups ag ON drs.group_id = ag.group_id; -

Once we’re in a

SYNCHRONIZEDstate, set the global primary (NY-SQL04) to aSECONDARYrole1 2ALTER AVAILABILITY GROUP NYOnly_TAG SET (ROLE = SECONDARY); -

Now the AG is not available for write traffic. Test that we’re ready to failover by executing the following on both the former global primary (NY-SQL04) and the soon to be new global primary (NY-SQL03). This query verifies that the LSN is the same on both servers.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10SELECT ag.name, drs.database_id, drs.group_id, drs.replica_id, drs.synchronization_state_desc, drs.end_of_log_lsn FROM sys.dm_hadr_database_replica_states drs INNER JOIN sys.availability_groups ag ON drs.group_id = ag.group_id; -

Perform the failover to the new global primary (NY-SQL03)

1 2ALTER AVAILABILITY GROUP NYOnly_TAG FORCE_FAILOVER_ALLOW_DATA_LOSS; -

Change the state of the distributed availability group back to

ASYNCHRONOUS_COMMITthis is done on the new global primary (NY-SQL03)1 2 3 4 5ALTER AVAILABILITY GROUP NYOnly_TAG MODIFY AVAILABILITY GROUP ON 'NYOnly_AG' WITH (AVAILABILITY_MODE = ASYNCHRONOUS_COMMIT), 'AG-NYOnly' WITH (AVAILABILITY_MODE = ASYNCHRONOUS_COMMIT);

At this point, our first distributed availability group had failed over and things were writable again. Only 4 more to go!

We could capture exceptions and with Team City up an running, it was time to tackle the next DAG, Chat_TAG. We performed the same steps listed above, on that DAG. Chat was selected to be done next, because we use our chat platform internally, and having it accessible is very important. When I’m doing regular maintenance on the SQL Servers, the Chat_AG is one of the first AGs we failover, and that the pattern held for the DAG failover. After executing all the steps above, we successfully failed over Chat.

2 down, 3 to go! Time for the more critical stuff to be tackled.

To minimize impact for users, we did the failover during the latter part of the day. Next up in the failover process was the DAG that contained the Careers database. By doing this, it would mean the end of syncing to the reporting cluster. We knew it was going to happen eventually, and held off as long as we could. Our stakeholders knew this was part of this failover process. The goal was to be back online as soon as possible once the entire failover process was complete.

Before starting the failover, the old distributed availability group between the 2012 cluster and the reporting cluster was destroyed. This was done because we knew the syncing to the reporting cluster would stop when we failed over. There was no need to have this extra layer of complexity and strain on the NY-SQL04 server. After the HighAvailability_DAG was destroyed, we set the Jobs area of the site to read-only, replaced all the connections strings in the applications, and then rebuilt them. It was then time failover the new DAG, Misc_TAG. Again, everything failed over without any issues. The Careers database was writable again, we moved Jobs out of read-only, and we were now more than half-way done with the failover.

The final two failovers were for the StackOverflow_TAG and SENetwork_TAG distributed AGs. These meant that we were going to have a bit of downtime. We were also planning on doing them in rapid succession. These two distributed AGs contain all the databases that handle the entire network of sites, and we wanted to fail them over as fast as possible to reduce the downtime. We pushed all new connection strings, the apps were rebuilt, and we were ready. All sites were set to read-only and it was go time.

First up, was the StackOverflow_TAG, as this only had 5 databases, and we figured it’d be quicker than our problem DAG, SENetwork_TAG - aka the one with 354 databases. I destroyed the old distributed availability group going to the reporting cluster, and we began the process to failover this DAG. Thankfully we hit no issues with it.

We were in the home stretch for the failovers with only one left…the big one. We hit so many issues with this distributed availability group when trying to get it set up, we were concerned about what would happen when we failed over. Unable to wait any longer, I kicked off the steps above to start the failover. It moved to SYNCHRONOUS_COMMIT without any problems, the databases on NY-SQL04 all reported to be in a SYNCHRONIZED state, and I moved the server to be a SECONDARY role in the DAG.

So far so good. Now it was time to verify the LSNs between the two servers using:

|

|

Executing that query on both servers (NY-SQL04 and NY-SQL03) and trying to verify that the LSNs were the same on 354 databases was not what I’d call an enjoyable process. We would verify, then re-verify and something would change, so we’d verify again, and again. It took some time to figure out if we were in a good state to failover. Our goal was to not lose any data, but trying to make sure we had a match against all the databases was pretty tough. Once we were reasonably confident, we made the call that it was time to finish the failover of this DAG, so I executed the commands to failover the SENetwork_TAG. Once the failover command was executed, the new primary (NY-SQL03) came up just fine, and was responsive for us to query it. We were done with all of the temporary distributed availability groups, and all of the sites went back to read/write. Failover done!

We thought we were in the clear, but the former primary (NY-SQL04) was very, very angry. After the failover from NY-SQL04, the server was completely unresponsive to anything. All the databases locked, CPU spiked, we were hitting HADR waits, and we didn’t get any sort of response for more than 25 minutes. Thankfully, we weren’t overly concerned because we had a new primary that was working, and this would be completely rebuilt to Windows Server 2016. We made the decision to just stop the SQL Server service until I got around to the rebuild.

All of the failovers were complete and everything was running on the new Windows Server 2016 clusters. Our servers looked like this:

We still had two servers in the old 2012 clusters. NY-SQL04 wasn’t functioning as a SQL Server because we shutdown the SQL service post failover, and NY-SQL02 was a member of the temporary distributed availability group we just failed over. Those servers were going to be rebuilt the next day, so our focus turned to the reporting cluster. That cluster is used internally for applications, and we needed to get it back up as soon as possible for use.

Initially, we thought that if we recreated the distributed availability groups with the reporting clusters as a member, things would just pick back up and sync. We executed the following to recreate the two distributed AGs with the new cluster and reporting cluster:

|

|

After executing this and recreating the distributed AGs, we realized very quickly we were wrong about them starting to sync again. The reporting cluster wouldn’t sync. We tried kicking the databases with various commands, and even tried failing the reporting cluster over to the secondary server in Colorado and then failing back. Nothing was working. After checking the logs on the reporting cluster primary, NY-RPTSQL01, we found lots of errors:

Msg 3456, Level 21, State 1, Line 22

Could not redo log record (8278:53574:4), for transaction ID (0:8787310), on page (1:10082), allocation unit 72057594040811520, database ‘CareersAuth’ (database ID 23). Page: LSN = (8277:108566:2), allocation unit = 72057594040811520, type = 1. Log: OpCode = 6, context 1, PrevPageLSN: (8278:53568:2). Restore from a backup of the database, or repair the database.

Msg 3313, Level 21, State 1, Line 22

During redoing of a logged operation in database ‘CareersAuth’, an error occurred at log record ID (8278:53574:4). Typically, the specific failure is previously logged as an error in the operating system error log. Restore the database from a full backup, or repair the database.

Msg 3414, Level 21, State 4, Line 22

An error occurred during recovery, preventing the database ‘CareersAuth’ (23:0) from restarting. Diagnose the recovery errors and fix them, or restore from a known good backup. If errors are not corrected or expected, contact Technical Support.

Well, that stinks. It meant we’d have to rebuild the AGs on the Reporting Servers using a recent backup, and then try to get them to synchronize. We started restoring the databases that were impacted in a NORECOVERY state with a local copy so the restore process didn’t too long. Once the databases were restored, we executed the following on each database to get them syncing again:

|

|

While this all worked great for the primary reporting server, NY-RPTSQL01, we were not as lucky with the secondary server in the reporting cluster, CO-RPTSQL01. We already suffer from throughput issues with CO-RPTSQL01 and all of the de-synchronizing put all of the databases in a state that couldn’t be recovered. Unfortunately, all the databases would also have to be rebuilt by restoring copies, then altering them to set them as a part of the availability group. The big problem was we didn’t have a local copy in Colorado to restore due to all the other server moves (we had turned off daily backups), so we were going to have to copy the files from NY to CO to then restore on CO-RPTSQL01. That might not be a big deal normally, but we have databases that are several TBs and the move was going to take a while. I decided to call Day 9 done, and pick that process up in the morning, along with other clean-up.

Day 10 - Finishing Touches

After a couple of hours of sleep, it was time to try to finish this up. The list of things left to do was small, but was still quite a bit of work. We had to:

- Restore databases to CO-RPTSQL01 and get the AGs/distributed AGs syncing throughout the reporting cluster

- Destroy the temporary distributed availability groups on the new 2016 clusters

- Rebuild NY-SQL04 and NY-SQL02 - the last two servers in the old 2012 clusters

- Insert the newly rebuilt servers into the new 2016 Windows Clusters, install SQL Server, and add them to the AGs

- Turn on all t-log backups and daily full backups

- Put read-only routing in place on all availability groups

The goal was to get through the entire list same day, but that would be too easy. We ran into an issue immediately. Remember that NY-RPTSQL01 we got synchronizing at the end of Day 9 – it was lying to us. It said it was syncing, but it really wasn’t. If you queried the StackOverflow database, it was several hours behind the current production database…uh oh, something was broken. We tried to restart the SQL Service to see if that unblocked it, it didn’t. Unfortunately, the only way we were able to get it syncing again was to:

- drop, then restore the databases

- manually apply the t-logs to bring it up to date from the current global primary

- then after executing some SQL to kick the AGs, like magic, it would be synchronizing again

We did this for all the impacted databases on the reporting cluster primary, NY-RPTSQL01, and then still had to get CO-RPTSQL01 back online. Nick Craver jumped in and worked on the NY and CO reporting servers, while I started rebuilding the final two servers, NY-SQL04 and NY-SQL02. The rebuild of the final two servers went exactly as expected. Once it came time to put the servers into the availability groups, I took fresh backups from the primaries and restored those. I did this because we weren’t going to automatically seed an AG with 354 databases or a 3.5TB one (StackOverflow), and I wanted to manually apply as few T-logs to the databases as possible to bring it up to current time.

It may have taken all day, but eventually we fixed the reporting cluster and had all six of our main SQL Servers moved into the new Windows Server 2016 clusters. By the end of the day, Opserver was reporting green everywhere:

It was such a good feeling to have everything moved over. After months of planning, testing, and frustration from hitting issue after issue, plus a bug in SQL Server, it was incredible to see it all come to fruition.

Final Thoughts

Besides the upgrade to SQL Server 2017 from the year before, I had never even attempted something with this level of complexity or planning. This project involved a lot of juggling of servers, AGs/distributed AGs, application changes, and considering we don’t have maintenance windows at Stack Overflow, it was difficult to imagine how to pull this off without being down for an extended period of time. To know this entire thing was executed with only about 10-15 minutes of downtime for the public facing sites is pretty darn amazing, in my opinion.

I have some takeaways from this - most are common sense, but I need to repeat them for my own sanity:

-

Test, re-test, and then test some more. The initial plan was to jump from the lab to prod, the rebuild of our development environment was unexpected. I also didn’t think this upgrade would break our development environment, but by doing these intermediate steps we found several bugs in our deployment process which we might have hit in production.

-

Have a lab environment, if possible. Between creating new lab environments and using my existing lab environments, I was able to work through all the different scenarios I figured we would hit in production. Of course, I wasn’t able to test at our scale and find the SQL Server bug, but I felt confident the steps I planned would work for the failovers.

-

Rely on your team. While I’m the only official DBA at Stack Overflow, there were times when I was at a loss on how to fix some of our issues with Foreman, Puppet, and needed extra hands. I can’t thank my team enough for stepping in and jumping into hangouts with me when I was stuck or something broke.

-

Remember that no matter how much you plan, something is going to go sideways. We had a ~35 page planning document that I wrote and none of that mattered when we hit the bug with availability groups.

-

Try not to stress out over the things out of your control. I hit roadblock after roadblock during this project, and felt that I was letting my team down by not moving it forward faster. When you expect a project to be done in one month and it takes about four, it’s hard not to feel like you’re failing and be stressed out over it. Each issue (failed drives, bugs) moved us forward and we improved our process, even if it was incredibly slow. In the end, we were in a much better situation because we squashed bugs and moved to better software. Keeping perspective on the end-goal is something to remind yourself when in these types of situations.

-

Keep notes as you’re going through a deployment like this. Every day write yourself a recap of what transpired that day, so you remember what went well or what broke. Unfortunately, I didn’t do this during the production part and spent a lot of time going through chat transcripts trying to remember all the steps and roadblocks we hit to document in this post.

I’m hoping this is helpful to someone who needs to go through this type of upgrade. Now that this project is done, I guess it’s time I start thinking about upgrading to SQL Server 2019.